Gimmicks About Gun Safes

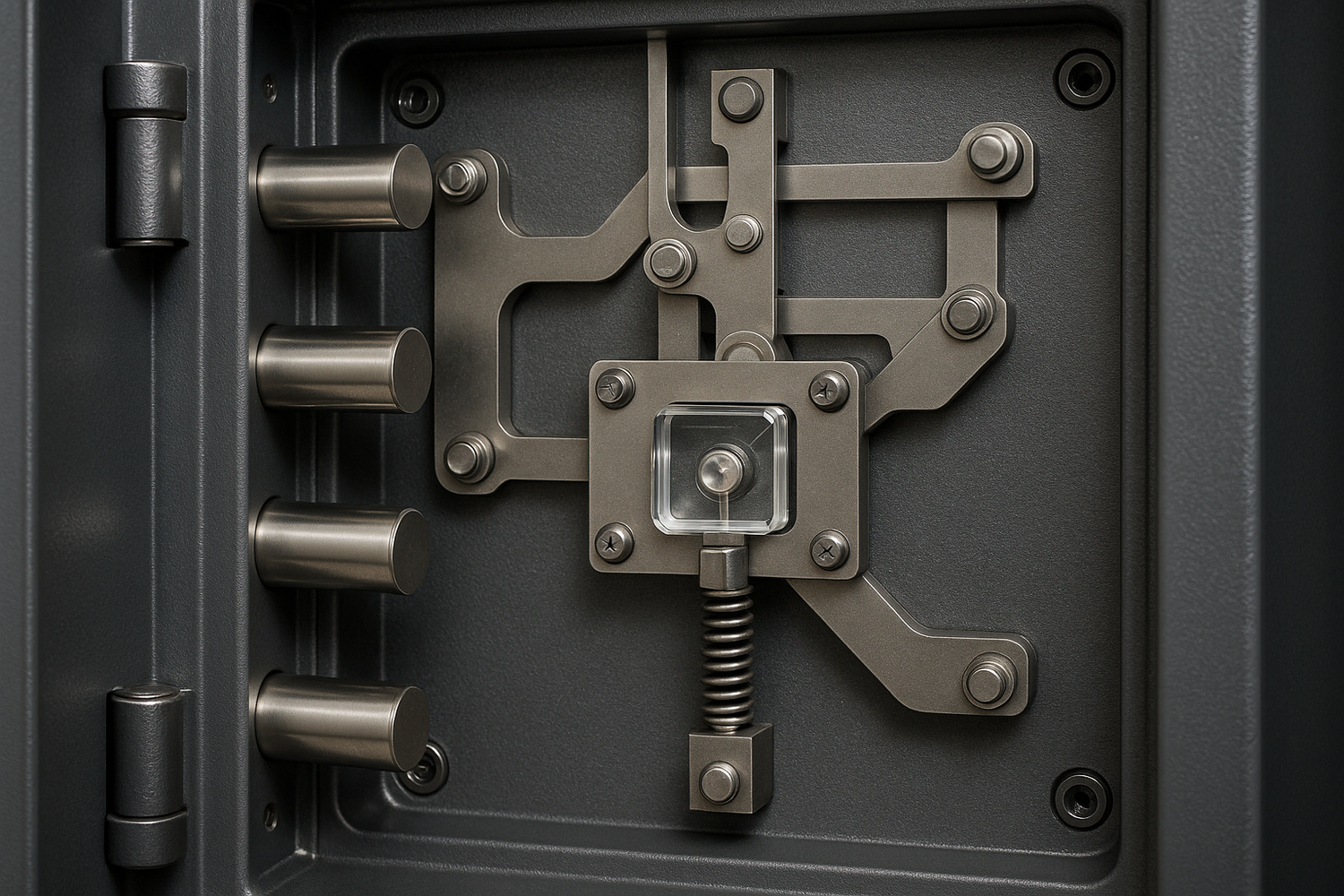

Handles Placed In The Middle Of The Door

Some safes feature a large, decorative handle positioned in the middle of the door—often a 5-spoke design. While it may look appealing, this placement is highly impractical and creates several vulnerabilities. Because the handle lacks shaft support in this position, the clutch can loosen over time and begin to wobble. To compensate, manufacturers use clutches and shear pins in the linkage system, but these parts are designed to break under force. Unfortunately, that means the safe can sometimes be compromised by simply forcing the handle up and down—or even by a child tugging on it while locked, which could lead to an unexpected lockout requiring a locksmith. Additionally, placing the handle in the center requires more moving parts inside the door, cluttering the mechanism and increasing the chances of failure. The most reliable linkage designs position the handle closer to the left side of the safe (while facing it), minimizing unnecessary parts and reducing long-term risks.

Too Many Moving Deadbolts

Some safes advertise an impressive number of moving deadbolts, but more doesn’t necessarily mean better. For example, commercial money vaults nearly the size of our 2822 safe often carry one of the highest security ratings, TL-30, and they typically use only three moving locking lugs—none positioned on the top or bottom of the door. Their strength comes from a well-engineered locking assembly combined with heavy, thick steel, not from an excess of bolts. Gun safes should follow the same principle. Security isn’t about how many deadbolts a manufacturer can fit into a door; it’s about the quality of the locking mechanism and the thickness of the steel body. A safe with dozens of deadbolts but thin 10-gauge (or weaker) steel walls can still be breached through the sides, no matter how strong the door looks.

Oversized Deadbolts (Long, Flat, Thick or Wide)

That bolt looks fancy but it's just held on by a screw and flimsy angle iron. Some manufacturers advertise extra-long, wide, or thick deadbolts as if bigger automatically means stronger. In reality, strength comes from proper internal support and solid steel construction—not bolt size alone. With a well-designed locking system, as little as a quarter-inch of bolt engagement can keep a door secure. Oversized bolts may look impressive, but without proper support they’re mostly for show and more prone to damage. In fact, something as simple as closing the door on a rag or rifle strap can strain the mechanism and lead to long-term issues.

Weld Quality

On many safes, the welds securing the lock bolt assembly and body are thinner or weaker than they appear. While they may look sufficient from the outside, poor welds compromise the overall strength of the safe. Ultimately, your deadbolts and safe body are only as strong as the welds that hold them in place.

2300-Degree Ceramic Insulation

While ceramic insulation can provide excellent fire resistance, many gun safe manufacturers cut corners to reduce costs. Instead of fully lining the safe, they may only insulate the top, bottom, or walls—leaving you to believe the entire safe is protected. Others use only a thin layer (about half an inch) of ceramic and combine it with sheetrock, yet still advertise high fire ratings.In real-world burn tests, these shortcuts consistently fail. Without a full and properly applied lining, the insulation simply isn’t enough to protect valuables in a serious fire.

Pictures of Fire Safes “Surviving” Fires

Be cautious when looking at pictures of safes that supposedly endured a house fire. In just three and a half minutes, a real house fire can exceed 1,100 degrees—and temperatures continue to climb rapidly. Under these conditions, the first things to burn off a safe are the paint and decals, followed by the dial, which melts at around 530 degrees. Aluminum handles are often next to go.Another red flag is the environment shown in the photo. If wood studs are still standing nearby, or if the surroundings aren’t reduced to ash, then the fire wasn’t nearly as severe as it appears. Many of these “proof” photos are misleading and don’t represent what happens in a true, full-scale house burn. In reality, most fires are far less forgiving than the marketing suggests.

Palusol Door Seals

Palusol is a heat-activated seal that expands when exposed to high temperatures. While this sounds good in theory, a door seal shouldn’t have to heat up before creating a tight fit. Palusol comes in a standard thickness—about the size of two stacked dimes—which means the door and frame of the safe would need to align perfectly every time to avoid gaps. In reality, no single gasket size can fit all safes with precision. A properly designed safe uses a custom-fit gasket that seals tightly from the start, without relying on heat to expand. Another drawback is that Palusol is typically rated for only one hour of fire protection, and its rating is not UL-certified.

Combo Box Mount, Combo Box, and Hard Plate

To cut costs, many safe manufacturers skip installing a proper raised mount for the combination box and instead weld the hard plate directly to the door. This shortcut significantly weakens security, since a welded plate without full support can be broken more easily. In addition, some hard plates aren’t fully hardened, making them even less effective. What you often can’t see is that many safes also rely on inexpensive, residential-grade locks. By contrast, a true Group 2 combination lock is built for durability and security, offering far superior performance and longevity—designed to last for generations.

Waterproof Gun Safes

When companies advertise their safes as “waterproof,” the claim usually means protection only up to a certain water depth and for a limited amount of time. Be cautious of vague or misleading explanations, such as “the fire seal expands under heat” or “the safe gets so hot that water turns to steam before it enters.” These statements are marketing spin, not real protection.

In fact, only one RSC has ever been specifically designed to resist water, and even then its rating was limited to just two feet of water for 72 hours. To make matters worse, that same safe is also one of the flimsiest RSCs on the market—hardly a reliable solution for either flood or burglary protection.

Double-Sided “Thick Gauge” Doors

Some safes advertise double-layer or “composite” doors as if both sheets of steel provide equal protection. In reality, only the outer sheet is defending the critical linkage parts. Once that first layer is breached, the internal mechanisms are exposed—meaning the second sheet adds little real security.This is why the outer layer of steel is what truly matters. Always pay close attention to the actual gauge of the first sheet, and be wary of the word “composite” when manufacturers describe total door thickness. It often disguises a thin outer layer paired with filler material that adds bulk but not real strength.

"Super Thick" Doors

Some gun safe doors measure up to six inches thick, but don’t be fooled—many are formed from thin 12-gauge steel with large amounts of empty air space inside. This design looks impressive but offers little real security. Whenever a company advertises door thickness without also specifying the steel gauge, take it as a red flag. The true strength of a door comes from the thickness and quality of its steel, not from padded dimensions or hollow space.

Fire Ratings

Fire ratings are one of the most misleading claims in the gun safe industry. Some manufacturers advertise inflated ratings that magically “double” when tested by a different facility. The problem is that most of these tests aren’t standardized—they’re conducted by independent labs hired by the manufacturer, often under conditions designed to produce favorable results. Unlike UL (Underwriters Laboratories) fire testing—which includes cooling periods and “point of no return” thresholds—these alternative tests often stop right before the contents would be destroyed. This makes even poor insulators, like thin layers of sheetrock, appear effective. In reality, most RSCs (Residential Security Containers) on the market do not carry a true UL fire rating, regardless of whether they’re lined with fireboard or other materials.What you’re left with is exaggerated “burn time” claims that don’t reflect how a safe actually performs in a real fire. Many companies rely on as little as $30 worth of sheetrock to market their safes as fireproof. By contrast, we test our safes in actual house burn-downs—because real fires demand real results.

Lifetime Warranties

“Lifetime warranty” sounds reassuring, but in the gun safe industry it often comes with hidden limitations. Many companies highlight what’s covered while leaving out what can void the warranty—such as changing the combination, making cosmetic alterations, over-torquing the handle, slamming the door, or failing to have the lock professionally maintained. In many cases, even with a “lifetime” policy, the coverage on critical linkage parts lasts only a year. That’s especially concerning for safes designed with lots of moving linkage, since those components are the most likely to fail over time.

Don't Be Fooled By "Awards"

Some safe manufacturers boast about impressive-sounding accolades—like being "awarded UL Residential Security Container (RSC) status" or holding "multiple U.S. patents for innovative security features." But here's the truth: these aren't awards in any meaningful sense. Manufacturers pay for UL testing and patent applications, and those costs are simply passed on to you. What’s worse, the UL RSC standard sets a surprisingly low bar. Passing it doesn't mean a safe is truly secure—it just means it survived a very limited set of tests. Case in point: that viral video of two guys opening a safe with a crowbar? That safe was a UL-rated RSC. Bottom line: Don’t let buzzwords and technical-sounding claims replace real research. Focus on what actually protects your valuables—not what looks good in a brochure.

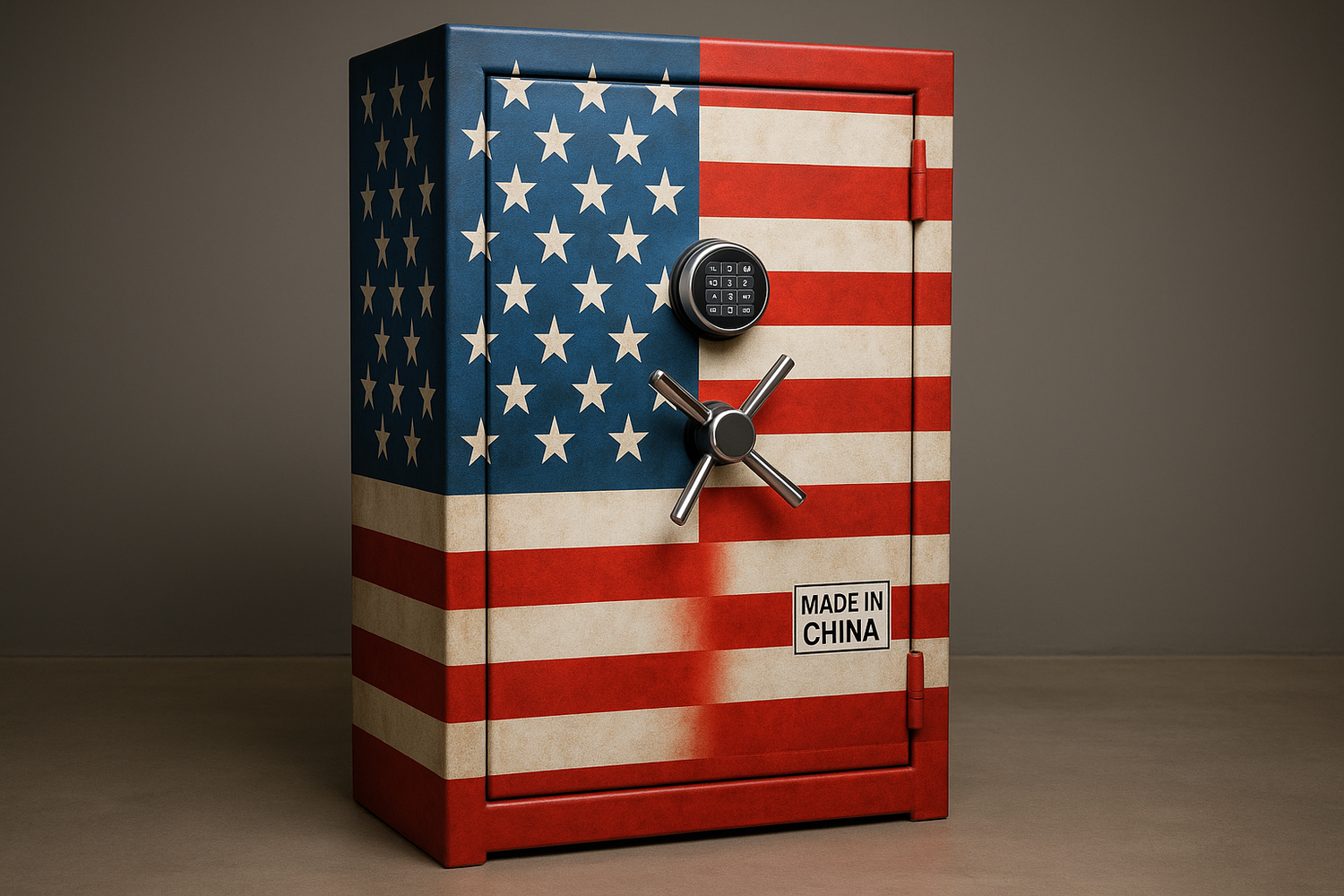

100% American Made- So They Say

Some safe companies proudly claim their products are “100% Made in the USA,” but the reality can be very different. One example: Patriot Gun Safe told customers their safes were entirely American-made—yet most of the majority of the safe came from China. They refused to allow visits to their so-called manufacturing facility, and eventually went out of business, leaving thousands of customers and suppliers out of money. Unfortunately, they’re not alone. Some companies do the bare minimum—like painting or assembling imported parts in the U.S.—and still slap on a “Made in America” label. If buying American-made matters to you, don’t settle for vague claims. Ask direct questions like:

- “Where are your safe bodies manufactured?”

- “Where are your safes assembled?”

- “Do you import any parts?”

Only then will you get a clear picture of what you're really buying.

Hardplates And Relock's - Half The Story

Some safe manufacturers proudly promote their hardplates and relockers as critical security features protecting the combination lock. But look closer — many of them completely ignore a major vulnerability: the internal linkage that connects the lock to the rest of the safe's locking mechanism. The linkage is just as critical as the lock itself, and it’s a primary target for attackers. If it’s not properly protected, bypassing the lock becomes significantly easier — no matter how tough the hardplate is. When evaluating a safe, make sure:

- The hardplate protects both the lock and the linkage.

- The safe includes an independent relocker (not one built into the lock).

- The hardplate is not welded directly to the door — doing so reduces its effectiveness and defeats its purpose.

If a manufacturer skips over these details, that’s a red flag.

The Truth About Sheetrock Fire Liners

Many safe manufacturers use sheetrock (also called drywall or other fancy names) as their primary fireproofing material. What they don’t tell you is that this material was originally designed for building construction — specifically, to slow the spread of fire in walls, not to insulate valuables inside a sealed container. Sheetrock is not a true insulator. It’s meant to block fire, not to protect against the extreme internal temperatures that can destroy sensitive items in a safe during a fire. If real fire protection matters to you, look for safes that use genuine insulation materials — not just repurposed building supplies with misleading labels.

Glass Relockers

Many safe companies highlight their use of glass relockers—thin glass plates designed to trigger additional locking mechanisms if shattered during a drilling attack. While this sounds impressive, what they don’t mention is how fragile these components can be. In fact, something as simple as slamming the door too hard can accidentally break them, leaving the safe permanently locked—even to the original key or combination.

Gun Count

Be cautious with the “gun count” manufacturers advertise. A safe marketed as a 16-gun model may only have 12 actual slots—and of those, you’ll be lucky if 10 rifles fit without cramming. Sturdy Safe lists the true number of usable slots in each model and designs interiors with enough space to accommodate rifles with scopes and other attachments.

Size Allusions

Some safe manufacturers exaggerate dimensions and capacity in ways that can be misleading. For example, a safe advertised with a 13.5" depth may only offer 11" of usable shelf space. Other common tricks include: oversized spoke handles counted as part of the depth (adding up to 3"), door organizers that reduce interior and gun rack space by around 4", inflated gun counts (as noted above), and even overstated weights. It’s no surprise many people say you should “buy bigger than you think you need”—because the real usable space is often less than advertised.

Non-Exposed Hinges

Some manufacturers claim that hidden hinges are just as durable as exposed ones—but that’s not the case. Concealed hinges are often vulnerable and can be damaged simply by slamming the door open. Exposed hinges, on the other hand, provide greater strength and make it possible to remove and rehang the door with ease—a feature known in the industry as a “serviceable door.”